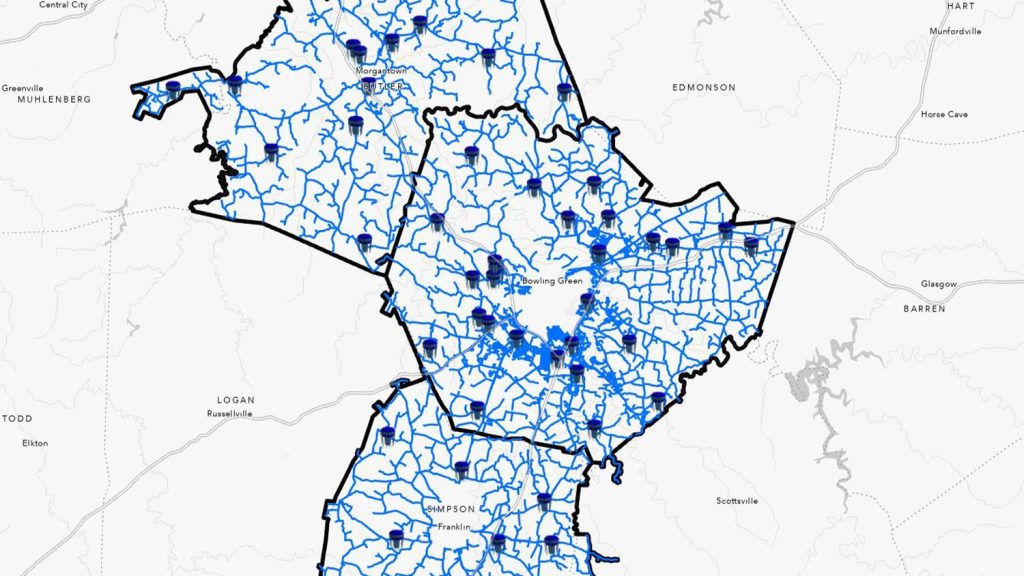

About an hour northeast of Columbia, South Carolina, Cassatt Water Company is a historic company originally incorporated in 1969 as a not-for-profit. In 2014, it converted to a Special Purpose District and is now officially called Kershaw County and Lee County Regional Water Authority, doing business as Cassatt Water. Today, Cassatt Water provides drinking water to a majority of Kershaw and Lee counties and small portions of Lancaster and Sumter counties. With a little over two dozen employees, their utility covers an impressive 764 square miles, including over 800 miles of water main. Every day, Cassatt Water produces two to three million gallons of drinking water to serve approximately 24,000 customers (mostly residential).

Video Recap

A Brief History of Cassatt Water’s System

Like many water utilities, Cassatt Water is experiencing a trifecta of change: First, its system is growing steadily in rural areas. Second, its veteran workforce with the most field experience is starting to retire. Finally, the demand for modern technology from newer employees with less field experience is increasing. When Chief Operations Officer John Watkins started working at Cassatt Water over 36 years ago, he stored system knowledge just in his head.

“Back then you had to remember everything,” Watkins said. “There wasn’t even a lot on paper, and there were no electronics.”

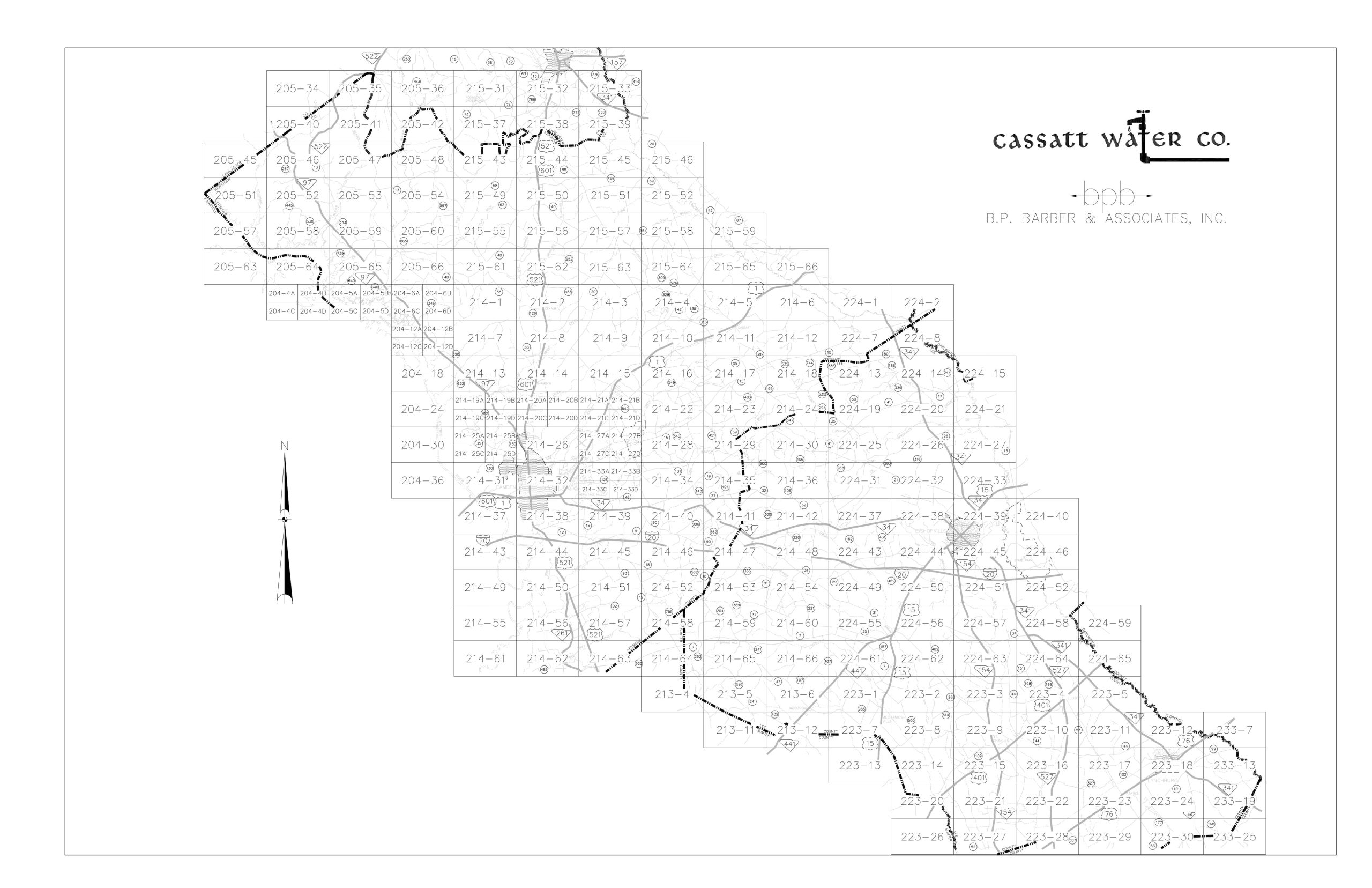

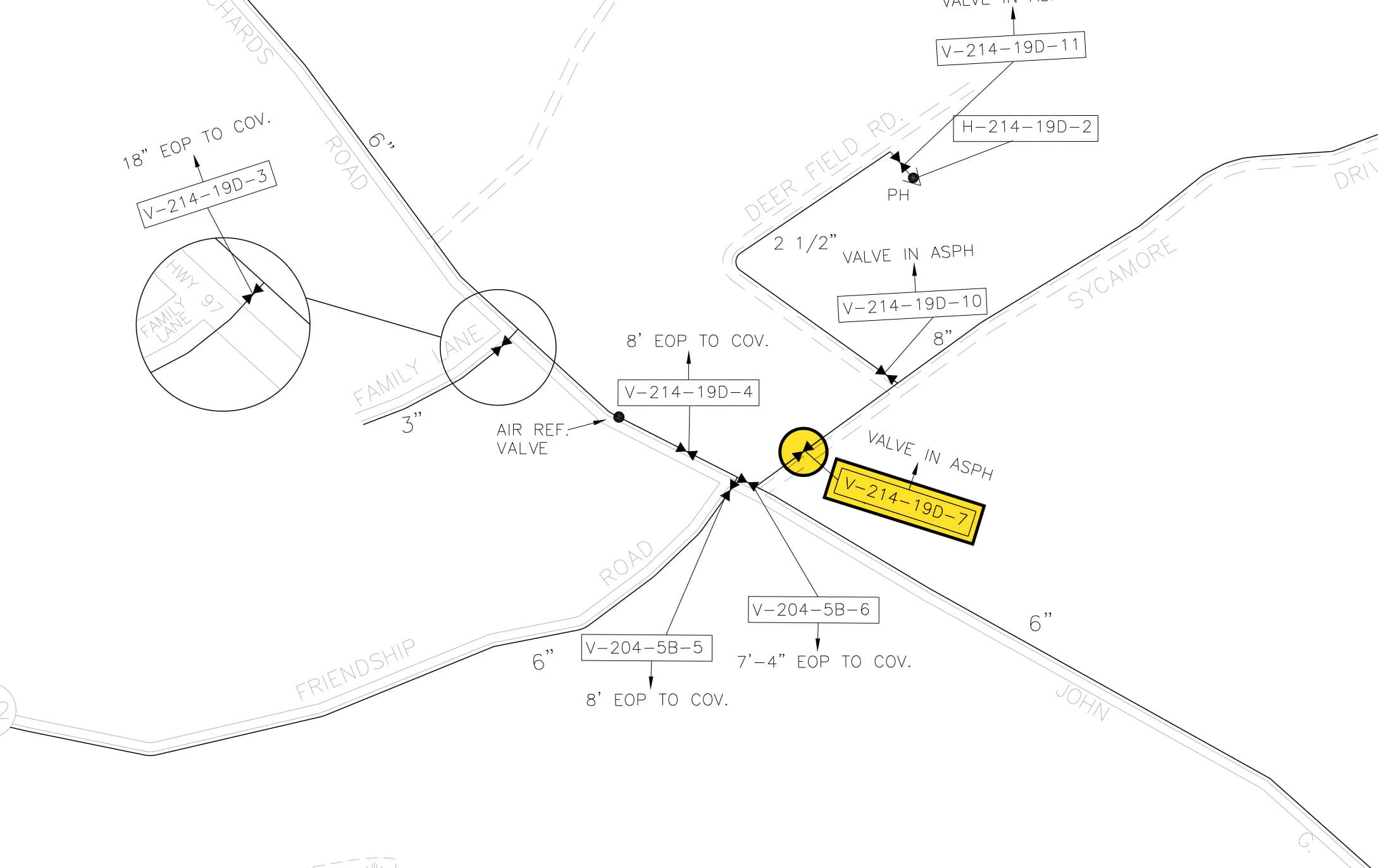

For decades, Cassatt Water relied on paper mapbooks to capture and refer back to asset locations. These were two-inch-thick, printed CAD drawings that, while conceptually accurate, offered only approximate valve locations and were time consuming to browse and search. “They were bulky, and you had to keep going back to the index because not everything could be shown to scale on a single page,” Watkins said.

Using the mapbooks, new staff needed time to find not only their own location on the printed maps, but also the locations of the assets themselves. Sometimes based on the grid system of the map book, nearby locations would be separated by hundreds of pages. The expansive size of the Cassatt Water system added tremendous time to locating assets.

“This was frustrating, especially in the case of leaks,” Watkins said. “Imagine that you know the general location of something, but you can’t find it. You can’t find that valve to shut down that pipe and fix the leak faster. That is really frustrating for us.”

The mapbooks were also outdated, lacking new constructions and sometimes listing assets as “current,” or “in use”, when they had been abandoned (a term used for assets no longer in use).

“Most of our guys who were going out there to fix leaks were newer employees, and they relied heavily on those old mapbooks to find assets,” Director of Engineering Nathan Ward said. “They were missing so much information.”

Back in 2016, Cassatt Water had hired a third-party consultant to digitize the original mapbook and CAD drawings from newer projects into a digital geographic information system (GIS) using Esri’s ArcGIS®. While creating a digital map in GIS was an improvement, the data in the maps wasn’t geographically accurate because they were based on the original mapbook and CAD drawings.

“Getting CAD drawings into the GIS was great,” said Ward, who used to work for the consultant before moving to Cassatt Water last year. “If you were to just look at the lines on the map, they looked great — until you started going out into the real world and trying to actually find the water main or valve.”

The Challenge: Location, Location, Location

“Imagine that you know the general location of something, but you can’t find it. You can’t find that valve to shut down that pipe and fix the leak faster. That is really frustrating for us.”

— John Watkins, Chief Operations Officer, Cassatt Water

Ward started to hear complaints from the field staff that the GIS wasn’t accurate. Valves on the map could be tens of feet down the road, on the other side of the road, or nowhere to be seen if the landscape had changed due to construction or vegetation.

Meanwhile, field crews performing maintenance or more crucially, responding to water leaks, needed to be able to quickly locate valves so that they could shut off water and perform the repair.

“The quicker you can get someone to your valves during a leak, the quicker you can cut the water off, and the quicker you can fix the leak and shorten the time the customers are out of water,” said Water Quality Manager John Bowers, who has worked at Cassatt Water for over 9 years. “It all has a domino effect.”

The field crews kept voicing their concerns that the GIS wasn’t accurate, so Ward dug into the utility’s records to see if he could improve the accuracy.

He discovered spreadsheets of legacy GPS data captured by a former employee that had never been processed. Hopeful, he uploaded these into ArcGIS — but the locations were still visibly inaccurate. Some valves showed up in the middle of the woods instead of on a street, for instance. “I knew I couldn’t use them,” Ward said. He knew he needed to overhaul the GIS and its location accuracy.

“I asked the field staff to give me a year to figure it all out and improve the GIS accuracy,” he said.

The Solution: Higher Accuracy for the Field

“The quicker you can get someone to your valves during a leak, the quicker you can cut the water off, and the quicker you can fix the leak and shorten the time the customers are out of water. It all has a domino effect.”

— John Bowers, Water Quality Manager, Cassatt Water

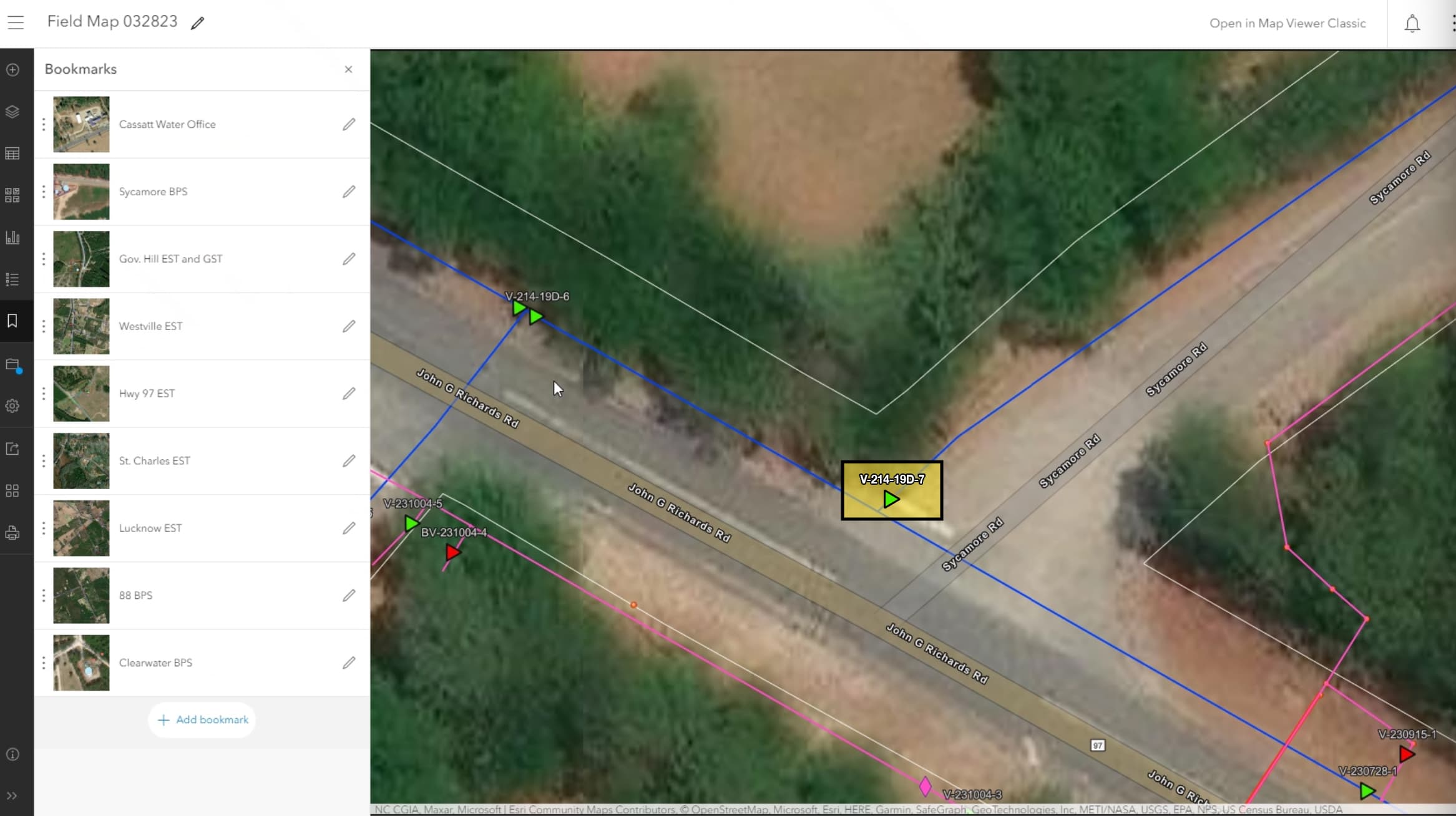

With no formal GIS background, Ward dove into ArcGIS training resources. He installed ArcGIS Field Maps (Field Maps) on company-issued Apple® devices and configured data-collection forms for the field. He also set up web map and geodatabase structures to better manage the asset locations and map change requests. Every field worker received a license so they could either update assets as they discovered inaccuracies or file map change requests for more significant issues, such as missing water main segments. In the office, Ward can review updates and either approve them in real time or assign them to someone for further investigation.

“What I love is that, if there’s an existing valve in the GIS, and the guys find it in the field, they can adjust the valve to its proper location, and now it is updated,” Ward said. “I might have to adjust the alignment of a line, but the update is instantaneous for everyone.”

With every field worker now equipped with the ability to update maps, Ward looked for a way to improve their iOS® location accuracy. While at a conference, he learned about a global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receiver that was compatible with Field Maps on iOS devices: the Arrow Gold+™. Made in Canada by Esri partner Eos Positioning Systems, the Arrow Gold+ sends high-accuracy locations via Bluetooth® to iOS devices and works seamlessly with Field Maps. Depending on what type of corrections service it is connected to, the Arrow Gold+ can provide accuracy ranging from submeter to centimeter-level. After evaluating the receiver, Ward subscribed to the South Carolina Real Time Network (SCRTN) differential correction service for sub-inch real-time kinematic (RTK) accuracy.

“It’s one thing to put points into a GIS,” Ward said. “But you don’t want to have to go out and map them again. That’s where having the Arrow Gold+ is so helpful. It brings the confidence to know that our valves are now very accurate.”

Today, all field staff are equipped with Field Maps on iOS, and two of them are trained to use the Arrow Gold+ for high accuracy data collection.

“Just a few months ago we were still using the old paper maps to locate valves in the system and set up new jobs,” Operations and Maintenance Manager Ashley Mangum said. “Now we exclusively use Field Maps. With the valves, hydrants, and meters being accurately located and displayed on the map, we have begun to trust the data which makes our job a lot easier and our response time much quicker.”

Initially, staff were skeptical about the new system, but once they saw the ease of use and quality of the location accuracy, they were on board.

“With everything that’s new, you hesitate on how well it will work,” Bowers said. “But as I got into it, getting the valves accurately located on the map just makes everything better. With the GPS coordinates putting us dead on the right spot, within a quarter of an inch, we can get close to the valve if we have a leak. It takes the guesswork out of it.”

The Results: Making Everything Better for the Next Generation

“What I love is that, if there’s an existing valve in the GIS, and the guys find it in the field, they can adjust the valve to its proper location, and now it is updated. I might have to adjust the alignment of a line, but the update is instantaneous for everyone.”

— Nathan Ward, Director of Engineering, Cassatt Water

According to Ward, the utility has so far updated about 10% of its valves in three months. “We still have a long way to go, but I think we’ve made a really good start on getting information into the GIS and getting it in accurately,” he said.

One of the biggest benefits has been getting institutional knowledge out of the heads of veterans like Bowers and Watkins, who Ward jokes are not allowed to retire until the GIS is perfect. Field staff with over 100 years of combined experienced have retired in the past five years, according to Watkins. Today, about a half-dozen crew members have less than two years’ experience. They still make a lot of phone calls to ask Watkins where things are when the legacy GIS points aren’t accurate.

“It’s really going to come to a point where I don’t think there will be a lot of phone calls once we’re done,” Watkins said. “The crews will just go right to the valves and other assets.”

That’s important for the next generation of workers, who Watkins and Bowers say will expect the maps to be reliable. “I can see the younger employees that we have coming up now, and they’re in the technology world,” Bowers said.

Watkins has noticed new employees starting to add value faster when using the GIS, as opposed to the outdated mapbook. “Any time you can take an employee that has very little training, hand them something like this, and say, ‘Go out and do this,’ and they can do it immediately — that is valuable,” Watkins said. “With this technology, it makes the new hires a lot more valuable from the beginning.”

The team has also started to use the technology to map new construction projects. Previously, Cassatt Water would rely solely on record drawings (CAD files or paper drawings) delivered at the end of the project to convey information about new developments or water mains. Now, Ward sends someone out proactively to map new assets as they are put in the ground.

“So now when a water main project or subdivision project is finished, we will already have it in our GIS,” Ward said. “All I have to do is change the layer property in ArcGIS from future to current, and the line color changes to blue, which indicates that the water main is now current.”

The team is already imagining new ways to use the technology.

“When you commingle the old-school experience we have with this new technology, it really does go a long way,” Bowers said. “Having everything correct in the GIS just makes this even more beneficial for the future. It makes it better for the ones coming behind us.”