Ground-penetrating radar and submeter GNSS units are helping archaeologists in Sweden detect previously lost monasteries that have been buried for centuries. In the process, they are redefining local history.

A Brief Introduction to Sweden’s Long History with Monasteries

Sweden’s oldest churches date back thousands of years ago and were built as the result of private initiatives. The first nunnery was erected in 1110, and by the year 1500 — just before the Reformation — there were a total of 11 nunneries in the country. The country’s first monasteries for male monks were built in 1143.

The historical importance of Swedish churches has been well documented over the years. The worship services that took place inside their walls were strict, and the priests in charge were granted with great power.

“If you didn’t go to church, you would be punished,” Swedish historian and archaeologist Christer Andersson said. “Where I live, there was a woman in the early 1700s who didn’t go to church on Sundays. She was sent to court!”

(In court, the woman explained that she simply did not understand the new language, a result of the territory where she lived having been conquered by the Danes in 1658.)

The first, and most important, buildings to go up were often monasteries

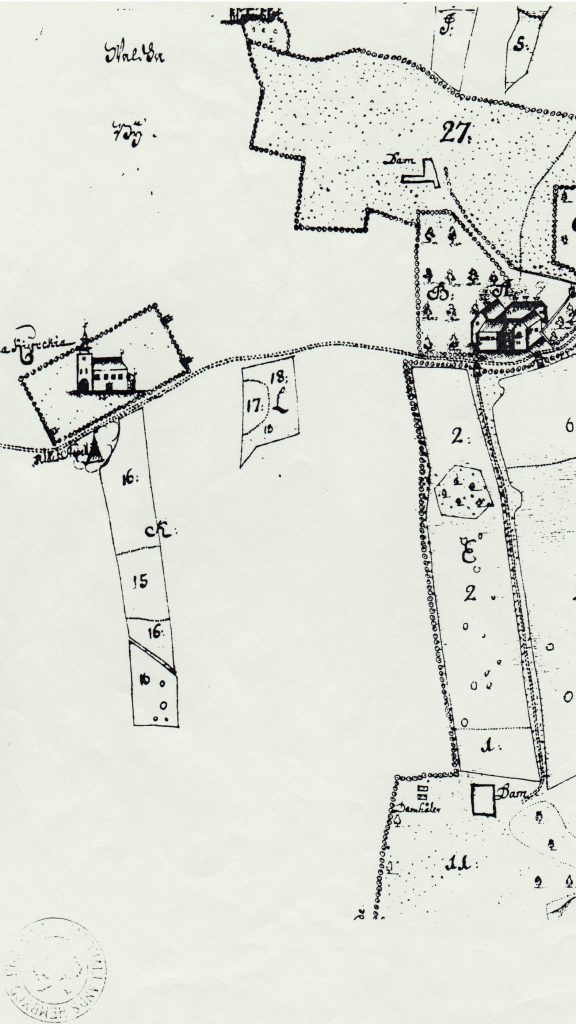

The monasteries were often the first, and most important, buildings to go up in any Swedish community. Yet today, due to the passage of time — including natural and man-made changes — some monasteries have been buried completely.

Some villages have an indication panel that points to where the monastery is believed to have stood. But these days, as archaeologists like Andersson are finding out, these signs are sometimes proven to be erroneous.

As local Swedes read more about the monasteries that were so critical to their histories, they have started to ask the question: “Where was the monastery that I have heard so many stories and legends of?” This is where professionals like Andersson come in.

But where are these monasteries now … exactly?

“This is the main thing,” Andersson said. “They want to know exactly where the monastery was, as well as its size and appearance.”

Finding the monasteries is the main task of Andersson and his company, Åsklosterprojektet.

There is also one more important thing Andersson has to consider: There are many old and interesting historical documents dating back hundreds of years, to the monasteries’ times themselves. These documents detail important facts about the monasteries, such as graves and other artifacts. Andersson takes all this into account when performing his work.

“For example, we have a letter from the Pope, dated around 1345, granting permission to King Magnus Eriksson and Queen Blanka to bury their three little princesses in Åskloster,” Andersson said. “So we will put a flower on their graves if we find them.”

About the Archaeologists: Astronomers Who Look Down

Christer Andersson is a radio astronomer.

“Instead of looking up,” he says, “I now look down.”

After retiring from his full-time work at the Onsala Space Observatory, Andersson started a new career finding monasteries. It all began with Åskloster, a Cistercian monastery situated 14 km north of Varberg, on the west coast of Sweden. The Åskloster monastery was built in 1194 and stood for almost 350 years onwards.

“Here we began our search for hidden churches and monasteries,” Andersson said.

“A friend of mine and myself were interested in finding the location of the monastery since we did not believe in the validity of the indication panel we found at the site.”

Andersson and his friend received funding from organizations that were interested in the community’s history, and then they got to work. Because of Andersson’s experience at the observatory, where he had to work with advanced electronic instrumentation, he was considered skilled for the project and earned the trust of the funding organizations . This was important, as geo-radar can be expensive.

“As hiring radar survey services can be very costly, we requested that we carry out the surveys ourselves,” Andersson said. “And for this, the foundations gave me some funds, because of their high interest in learning more about Åskloster.”

Andersson’s goal was to find portions of the monastery, such as buried walls, whose whereabouts were previously unknown. These walls could offer clues as to the exact structure and history of the ancient monastery.

“We can also do a georadar survey of an old church that was taken down so that a larger church would be built,” Andersson said. “Nowadays, it may happen that it is only possible to say: ‘somewhere in this place there was a church.’ But by finding the walls with a georadar survey, I can tell where it stood and how it looked. I can also tell if it had been rebuilt.”

About the Technology: What Do You Use to Find Buried Monastery Walls?

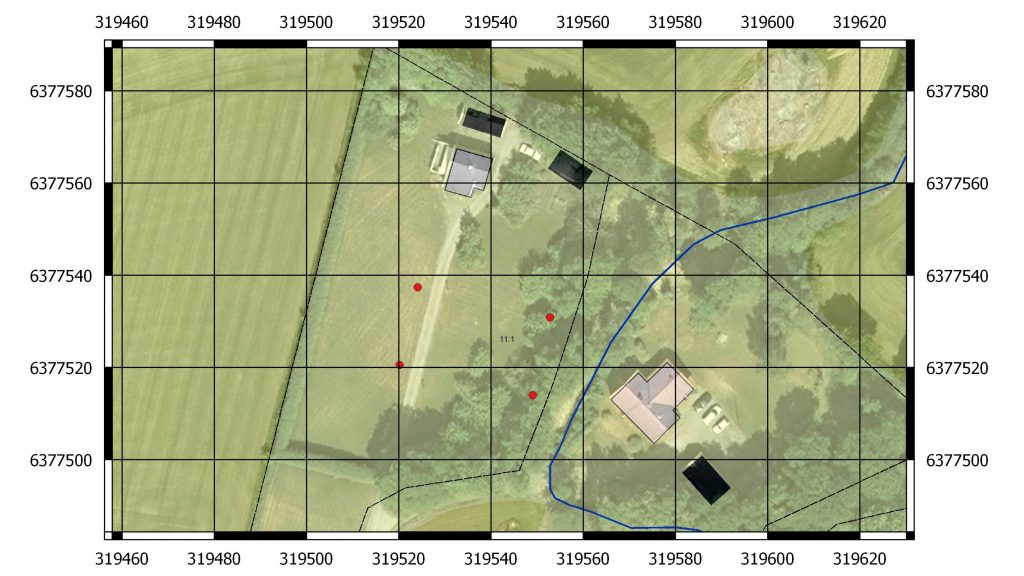

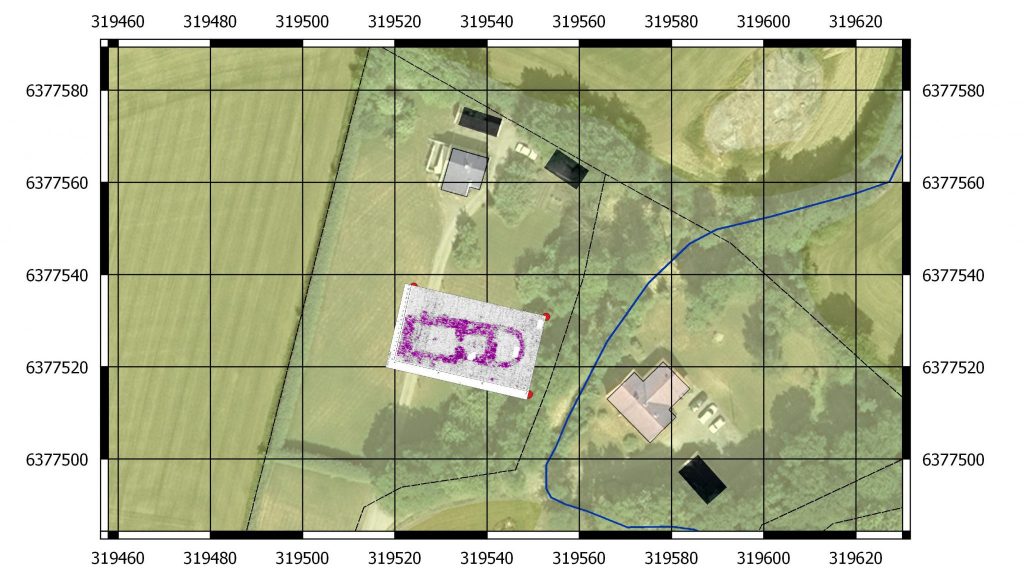

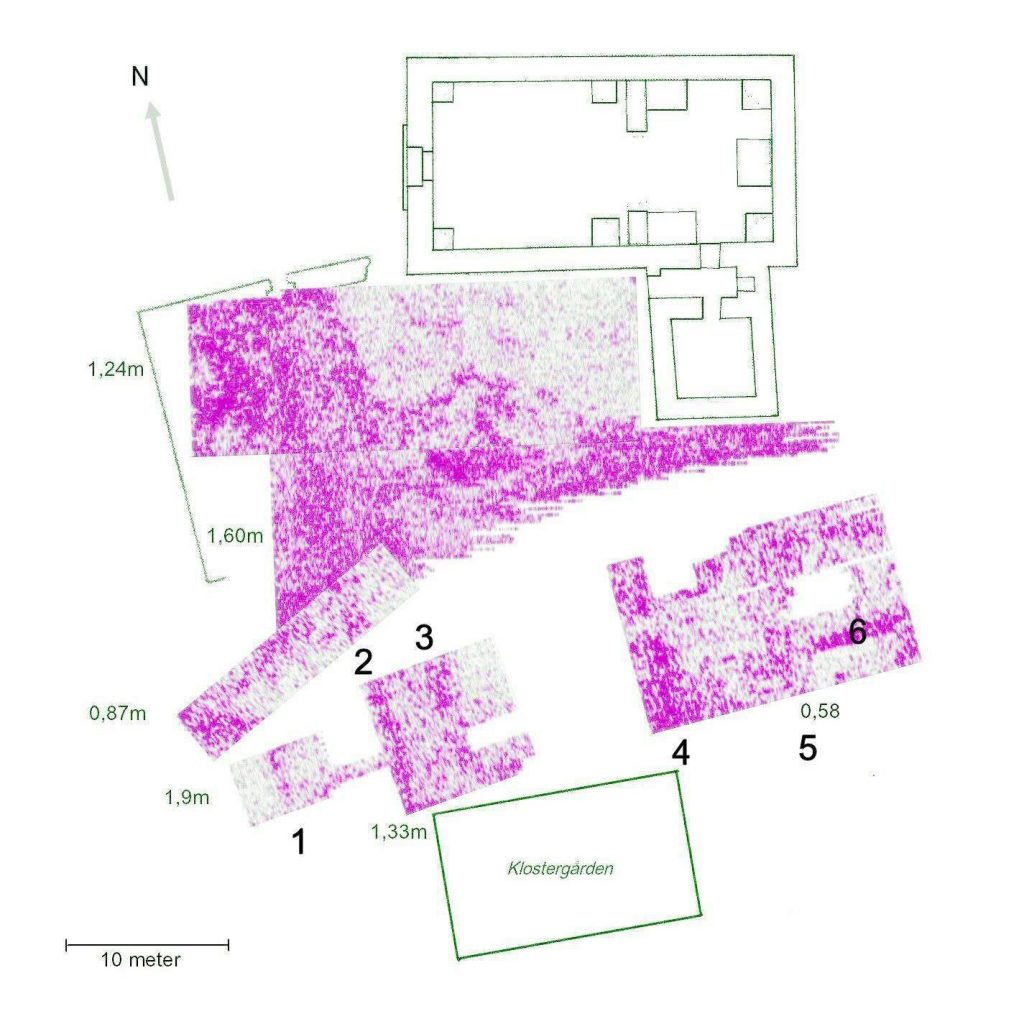

Andersson started his projects by dividing his archeological area into grids. The grid is comprised of parallel lines, which in one example might be about 20 cm apart from each other, along the scope of a rectangle that is perhaps 30 meters long by 20 meters wide.

Andersson will walk the grid while wheeling a variety of specific equipment designed to let him “see” below the earth’s surface, as well as capture the coordinates of what he uncovers.

“When the radar pulse hits something different from the earth, say a stone, it bounces back. Because we know how quickly the electromagnetic pulse goes into the ground, we can easily figure out the depth of the object.”

— Christer Andersson, Swedish historian and archaeologist, Åsklosterprojektet

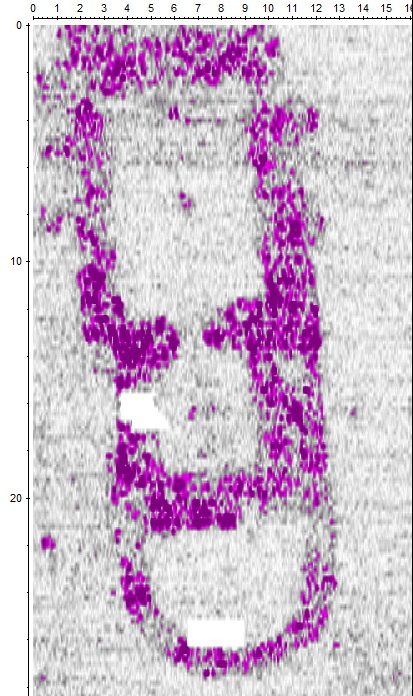

To “see” below the earth’s surface, figuratively speaking, Andersson walks the grid while sending ground-penetrating radar (GPR) pulses into the ground. Andersson acquired his GPR from Swedish company Geoscanners AB. The GPR measurements are triggered by an electronic distance meter connected to a wheel, which Andersson pushes. The GPR pulses penetrate the ground at every centimeter and to a depth of about three meters. This means that Andersson can walk the grid and produce a train of radar pulses for an entire volume of, in this case, 30 meters long by 20 meters wide by three meters deep.

Andersson says to think of the radar pulse like a rope attached to the wall. If you yank the rope, a wave will be emitted toward the wall, until it hits the wall and then bounces back.

“When the radar pulse hits something different from the earth, say a stone, it bounces back,” Andersson said. “Because we know how quickly the electromagnetic pulse goes into the ground, we can easily figure out the depth of the object.”

Back in the office, Andersson uses 3D imaging software to visualize the data he collected from the GPR. The software, Reflexw, allows Andersson to digitally “cut” 3D slices of the earth and determine various textures beneath the earth’s surface. So, without taking a single shovel into the ground, Andersson can create a glimpse into what excavators might find below the surface — as well as what might have happened to the structure over the years.

“I can see what has happened during the centuries, because we know how it should have been from the beginning,” Andersson said.

Andersson is able to provide a look into the ground. But to get the excavators to the right location, he must geo-reference his data.

“It is important to know exactly where you made the survey,” he said. “So I take the locations of the corners of the survey.”

This is where Andersson needed to access high-accuracy location in the field. Andersson researched GNSS receivers and decided to use the Arrow 100 submeter receiver.

“The Arrow 100 is a small GPS unit with a small antenna, it was easy to move in the field, and it got me the results I needed. I chose it because of the advanced technical data it provides and its price.”

— Christer Andersson, Swedish archaeologist, Åsklosterprojektet

“The Arrow 100 is a small GPS unit with a small antenna, it was easy to move in the field, and it got me the results I needed,” Andersson said. “I chose it because of the advanced technical data it provides and its price.”

Andersson used the Arrow 100’s out-of-the-box, 60-centimeter accuracy with EGNOS (Europe’s free GPS differential correction service). Although archaeologists require centimeter accuracy when excavating, Andersson needed only submeter accuracy for his phase of the work. By finding just the corners of a buried building with the GPS, Andersson can give a team of excavators everything they need to dig up ancient historical structures.

“If you have 60-centimeter accuracy, then archeologists cannot miss a stone wall,” he said. “So it’s perfect. I give the excavators this mark, and they can dig up the walls.”

Before taking the Arrow 100 out to the field, Andersson took it to the Onsala Space Observatory. At the observatory, Andersson identified known points and tested the Arrow’s accuracy. “And it passed the test!”

The Mystery of the Marstrand Monastery

Already known for his work in locating buried relics, Andersson was asked by Bohusläns Museum in 2014 to see if he could locate the Marstrand monastery.

“There were rumors that the church of Marstrand was the monastery, and that the monastery buildings had been at the churchyard,” Andersson said. “Already in 1746, this was written about. But later on, there was uncertainty where the monastery had been. I became interested in it.”

What was the Marstrand Monastery?

In the early 13th century, a thriving fishing business defined the coastal city of Marstrand. Herring flourished, and ships traveling internationally to and from Norway made a point to stop there.

By the end of the century, Franciscan monks had built a monastery. In a letter dated 1291, Pope Nikolaus IV mentioned a Marstrand monastery with at least 13 monks, in a location where today sits a grass-green cemetery.

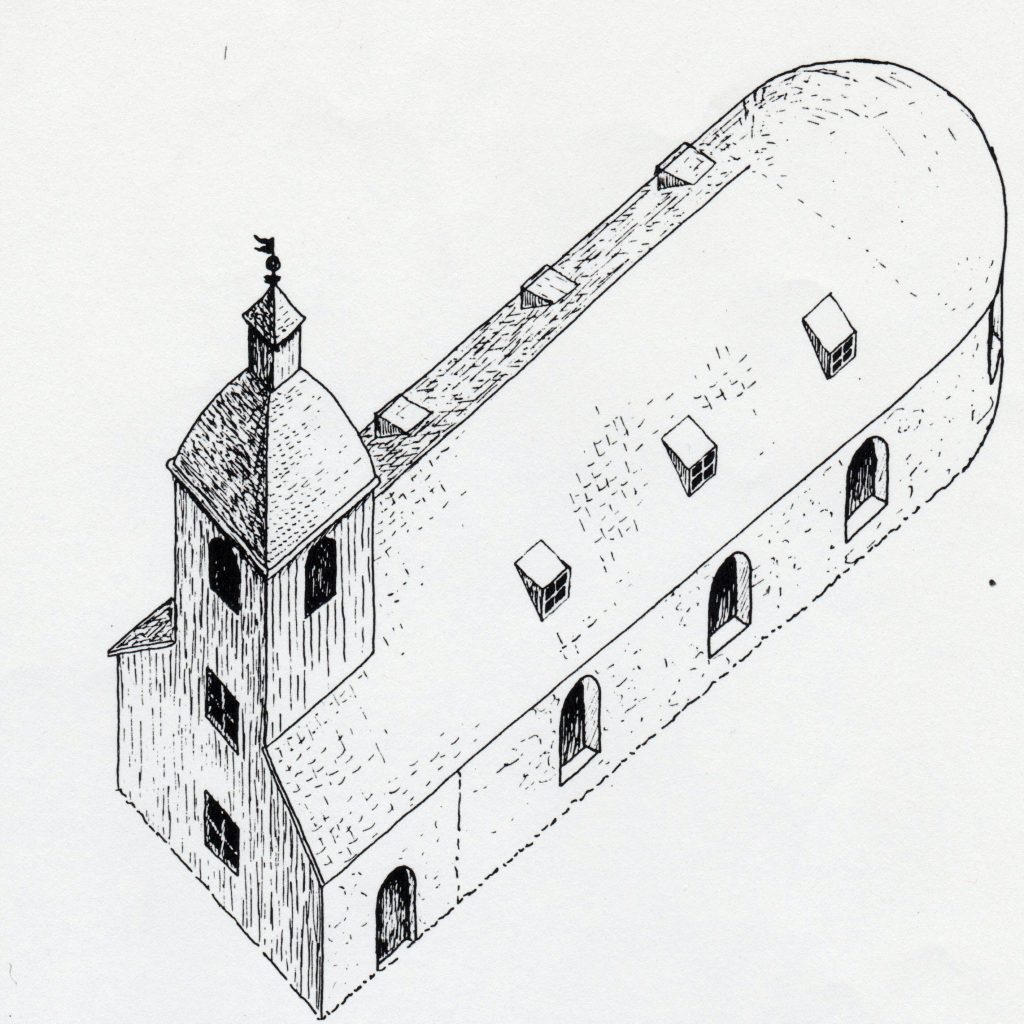

The Marstrand monastery is believed to have had ground walls of stone approximately 1.6 meters (or about 5 feet) wide. It may have had two stories built of timber.

When Andersson was called in to locate the historic monastery by the Bohusläns Museum, the structure was believed to have been situated in the Marstrand cemetery. Indeed, there was an absence of graves in the southern part of the cemetery, which indicated something had prevented graves from being dug there.

“But nobody knew for sure,” Andersson said. This is where Andersson focused his survey.

Results: Solving the Mystery of Marstrand and More

Today, there is a new understanding of where the Marstrand monastery stood.

In the southern part of the cemetery, Andersson and his team uncovered a structure that was likely the southern part of the monastery, where the monks would have had their dining room.

Based on Andersson’s findings, this part of the Marstrand Monastery was excavated in 2017. Excavators also found part of a stained-glass window dating to the period between 1350 and 1525, decorated with French lilies and sea leaves.

Since he first started finding churches in 2009, Andersson has led excavators and historians to the correct location of a dozen buried structures, including:

- Marstrand Monastery

- Riseberga Monastery

- Askeby Monastery

- Släp Old Church

- Fogdö Church

- Frillesås Old Church

- Hellerup — A property mentioned in 1300s

- Dragsmark Monastery

- Torup Old Church

- Wallen — A property known from the 1300s

- Kronohyttan — A place where there was a blast and where they casted cannons during the 1600s

- Bofors — A test ground for cannons circa 1880-1920, which was sought after in order to find out a foundation that had been used for testing cannons hidden below ground

- Aranäs — A town destroyed by king Håkon Håkonsson of Norway in 1256; however, a survey with intention to find Aranäs yielded no positive result

Andersson estimates there are many more structures to find, and he hopes that these may lead to the discovery of more historical relics, as well as cast a light on Sweden’s past.

“Where there are monasteries, there is often a lot of other things to discover,” Andersson said. “For example, fishing ponds and fishing spots, water channels, and a lot of other things. Åskloster was the largest building in the county at the time.”

So far, the local communities have been receptive to his work.

“This is all for the people who live here, who are interested in this,” Andersson said.

For more information on the Arrow 100, click here or contact Eos.