Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN) relies on volunteers, cutting-edge technology, and an innovative approach to preserving Florida’s archaeological resources

By some estimates, Florida’s sea levels have risen by six times the global average in recent years. This gives a greater sense of urgency to preserving the approximately 35,000 known at-risk cultural resources spread across 8,000 miles of Florida’s coastline. Florida’s cultural resources include everything from shell middens – refuse of daily life left by Indigenous peoples containing pottery, stone tools, and food remains hinting at thousands of years of occupation – to more modern historical structures such as buildings, cemeteries, and shipwrecks.

“You have to know what you have in order to manage it,” said Emily Jane Murray, Public Archaeologist for the Northeast Region of the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN).

FPAN is a not-for-profit established by the University of West Florida in 2005. Their mission is to promote the conservation, study, and public understanding of Florida’s archaeological heritage. Funded by state legislation and grants, FPAN emphasizes public outreach and community training, including volunteer contributions to archaeological projects.

“If you look at the Register of Professional Archaeologists, there are 147 archaeologists in the state of Florida,” FPAN Regional Director Sarah Miller. “But there are over 180,000 cultural resources listed in the Florida Master Site File. It is really impossible to keep an eye on them all.”

We’ve got models, which are limited, that say, ‘If you add five feet of water there, then a certain site will be wet. Unfortunately, we know by observation that these sites are already wet. So the real question is, how fast is this happening, and what do we do next?

The Challenge: Being Quicker than Water

In 2016, FPAN established the Heritage Management Scouts (HMS), a citizen-science program aimed at training volunteers to help survey 5,000-6,000 of the state’s most at-risk sites. These volunteers help document site changes, such as fallen trees and newly visible above-ground artifacts, which help FPAN know which areas require further study.

“We map anywhere these changes occur because this can help us pinpoint areas to go back to and complete more work,” Murray said.

But as sea level rises more quickly than models previously predicted, FPAN faces a growing challenge: How can they prioritize which sites to survey first, and how can they simultaneously build more accurate erosion models?

“We’ve got models, which are limited, that say, ‘If you add five feet of water there, then a certain site will be wet,’” Murray said. “Unfortunately, we know by observation that these sites are already wet. So the real question is, how fast is this happening, and what do we do next?”

Luckily, across the pond, Scottish archaeologists had recently asked — and answered — the same questions.

A Scottish Inspiration

With approximately 18,670 km (11,600 miles) of coastline, Scotland, like Florida, cannot ignore sea-level rise. The BBC estimates up to £400M ($495M USD) of Scottish infrastructure could be lost to erosion by 2050. Several years ago, the charitable research and conservation organization Scottish Coastal Archaeology and the Problem of Erosion (SCAPE) set out to map Scotland’s historical sites, model erosion rates, and prioritize the most at-risk sites for research, excavation, and study — in a way no one had done previously.

“SCAPE was a couple of steps ahead of us,” Murray said.

SCAPE focused on proactive collaboration among local officials and public outreach. They also piloted cutting-edge geospatial technology, best practices for data collection, database management, and workflows that proved both fast, accurate, and cost-effective. Not only did SCAPE map Scotland’s at-risk coastal sites, but they also modeled shoreline erosion rates with high accuracy. When FPAN visited SCAPE in Scotland in 2018, SCAPE shared their approach, technology recommendations, and data models with their international colleagues.

Phase One: Mapping Historical Sites

FPAN brought the recommendations back to Florida and secured funding for a pilot test.

“Our first goal was to collect information about what is happening at sites on the ground,” Murray said. “This way, we can determine what’s already been impacted, what’s being impacted the fastest, and what we should not worry about for a little while.”

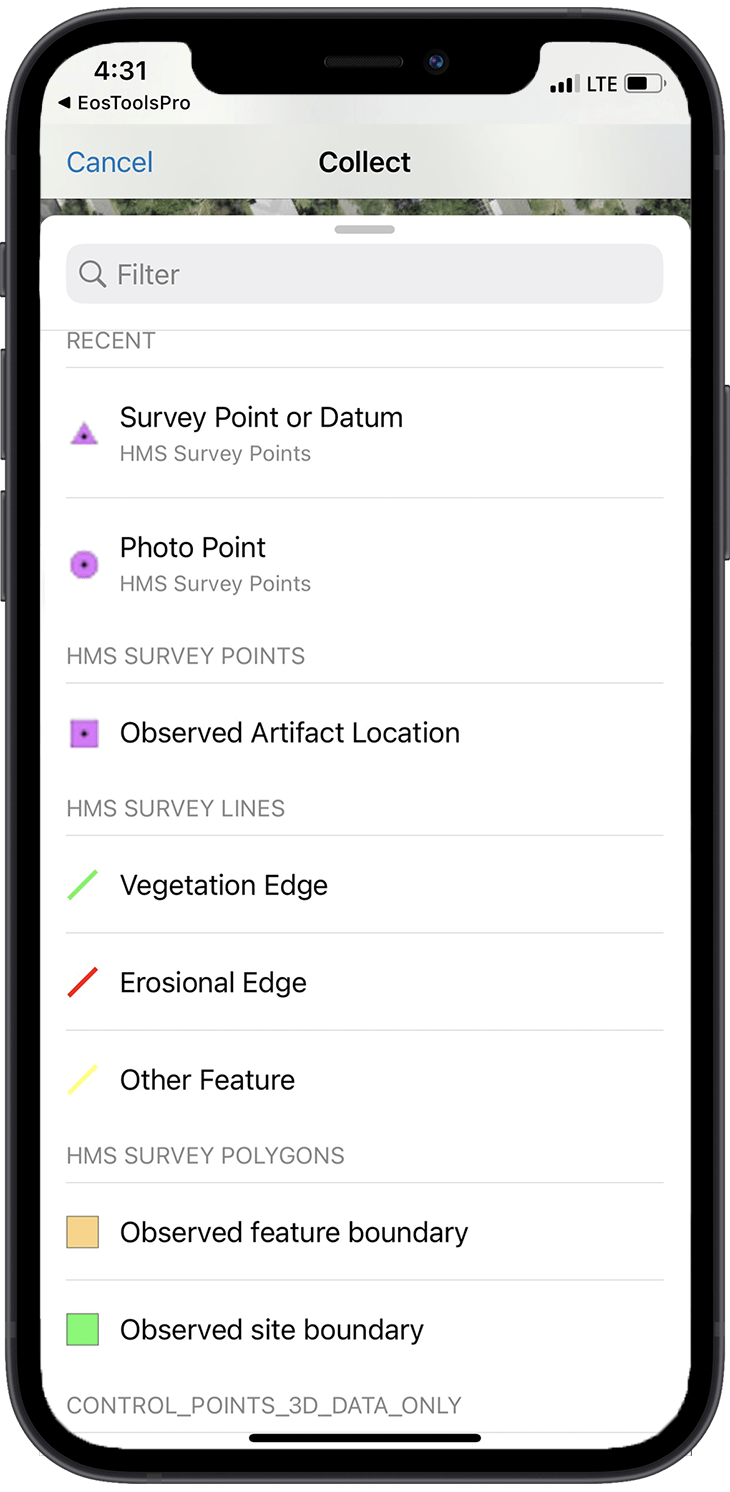

Following SCAPE’s lead, FPAN deployed Esri’s ArcGIS® platform for geospatial data management. SCAPE shared their database model for historical-site data, such as boundaries and artifacts. The ArcGIS Field Maps (Field Maps) mobile app allowed FPAN volunteers and staff to collect and update this type of information during site surveys. Field Maps provided tools to ensure field data collection was standardized, including programmable dropdown fields, check boxes, and required attributes, such as current conditions and photo attachments. The app works on either iOS® or Android™ devices.

“Field Maps let us create a simple form where our volunteers and staff can easily check boxes, collect information, and capture photos in the field,” Murray said.

You can just hand them the GNSS receiver, a phone loaded with Field Maps, and they are almost instantaneously operational. That’s a testament to how easy the Arrow GNSS receivers are to use.

To ensure at least 30-60 centimeter accuracy, FPAN provided surveyors with the same global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receivers that SCAPE was using: the Arrow 100® GNSS receiver made by Canadian company Eos Positioning Systems®. The Arrow 100 provides submeter-level location accuracy to Field Maps running on any iOS or Android device. The differential corrections source the receiver uses to calculate positions in real-time is called a satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS). SBAS signals are available for free in both the U.S. (via WAAS) and Europe (via EGNOS), among other regions worldwide. Out of the box, FPAN’s volunteers could get 30-60 centimeter accuracy with minimal training.

“You can just hand them the GNSS receiver, a phone loaded with Field Maps, and they are almost instantaneously operational,” Murray said. “That’s a testament to how easy the Arrow GNSS receivers are to use.”

By choosing an easy-to-use app, GNSS receiver, and consumer mobile devices, FPAN was able to make survey-like results achievable for any amateur field data collector.

“They’re doing real science, but their tools look like something they’re already used to,” Murray said.

Data collected in ArcGIS Field Maps appears in an ArcGIS Online map instantly at the office, where FPAN Database Manager Kassie Kemp performs quality control in near real time and prepares the verified information for submission to the state’s cultural resource database (the Florida Master Site File). With this workflow, FPAN is solving its first challenge: mapping every historical site efficiently, accurately, and resourcefully.

“Shoreline erosion is happening, and these sites are being affected,” Murray said. “Whether we get the information or don’t get the information, either way, we lose the site. Even as we are visiting them to track erosion, we are learning more.”

Visiting the sites to track erosion was, in fact, phase two of their program.

Phase Two: Modeling Erosion

There are as many ways to map a shoreline as there are to cut a sandwich. Do you map at high tide? Low tide? What if there’s a tree that’s fallen and creates an anomaly in the boundary?

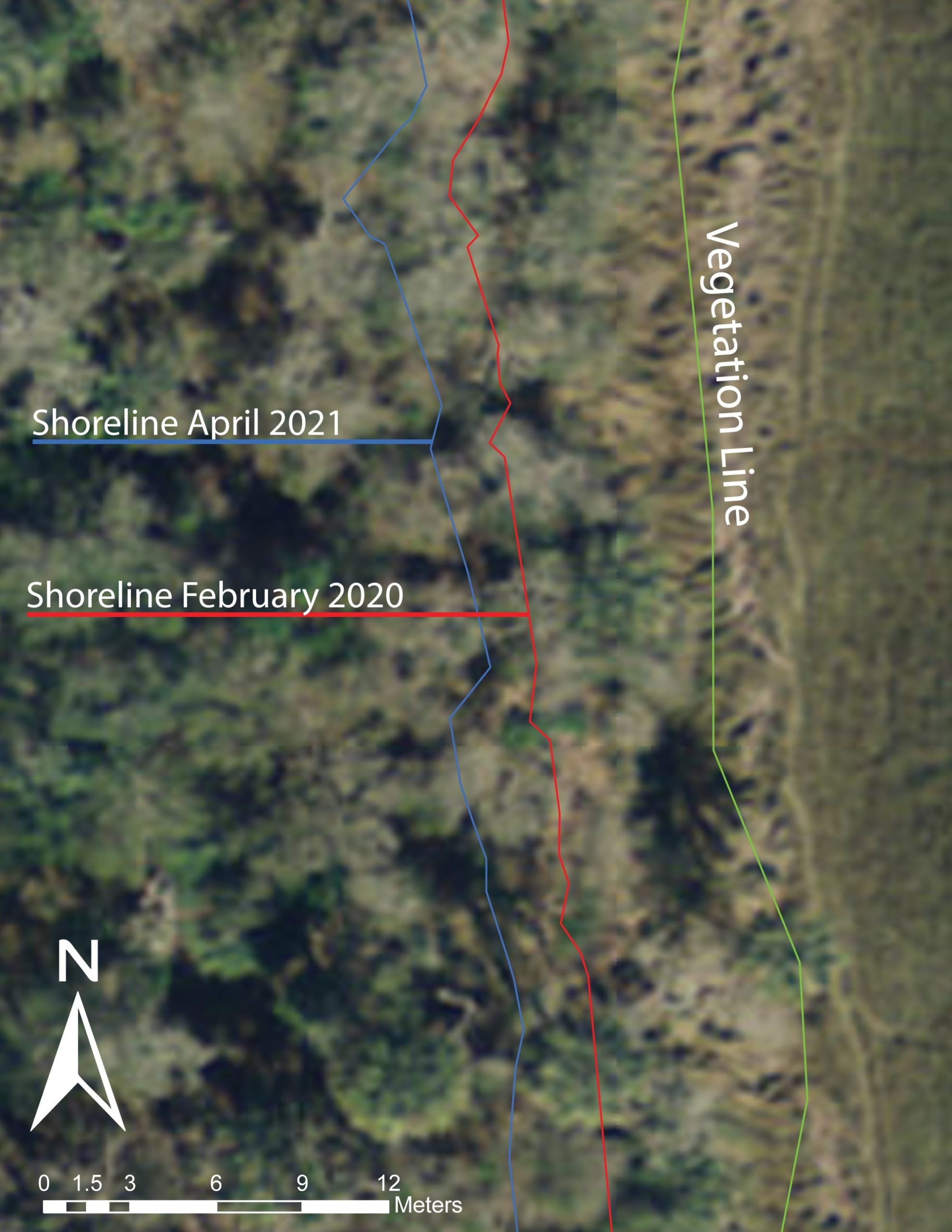

According to Murray, archaeologists at FPAN are interested in mapping the “upland erosional edge.” In other words, this is the edge they can consider the intact site. In some places, such as on a sand dune cliff, the intact edge is easy to identify. “In other places, like a marsh, it’s more ephemeral and open to interpretation.”

Erosion is just as variable. Sometimes, change is easily observable. At Shell Bluff Landing, for instance, near Jacksonville, the category 4 Hurricane Ian in 2022 drastically and permanently transformed the shoreline. Erosion was evident to the naked eye. But at other places, such as the average Florida marsh with palmetto thickets deeply rooted in place, erosion can be slower. Precision measurements in these areas might show only a few centimeters of change over time.

“If you can get to within a meter of a site boundary, you can usually see where the site is,” Murray said. “But tracking erosion requires a greater degree of accuracy.”

Last year, FPAN acquired funding from the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) System Science Collaborative to purchase two more GNSS receivers to test methods at the Guana Tolomato Matanzas (GTM) NERR. This time, they chose the Arrow Gold® GNSS receiver. Rather than relying on SBAS signals like its sister product, the Arrow 100, the Arrow Gold supports connection to the free local Florida Permanent Reference Network (FPRN) for its differential corrections. When connected to this real-time kinematic (RTK) network, the Arrow Gold is capable of providing centimeter-level accuracy both horizontally and vertically.

“This is one of the reasons we wanted the Arrow Gold since it is able to show us the erosion better, especially in areas that require change detection at centimeter-level,” Murray said.

FPAN’s goal is to map the coastline of each historical site at the GTM NERR once per year. They have compared these measurements over time to the Sea Levels Affecting Marshes Models (SLAMM) for the area. SLAMM is the industry-leading model used to predict future sea-level rise, along with related changes.

“The models are scary,” Murray said. “And in some places, we’re already seeing the changes.”

Recently, FPAN also acquired a FARO® laser scanner, which collects highly accurate spatial data at each historical site. This data is processed into point clouds and 3D models, georeferenced with high-accuracy coordinates from the Arrow Gold, and Murray’s team can now visualize and measure erosion volumes in 3D.

“This is one of the coolest things we’re doing with the Arrow Golds,” Murray said. “We can track more quantifiable shoreline loss by comparing the models through time and get a 3D rendering of all the sediment that has washed away.”

The Results: The Models Are Scary

To understand the past is to understand the present. We learn how we got here, and now, where we’re going.

Shoreline erosion is not a new problem in Florida. In fact, 8,000 years ago, Florida’s shoreline was twice as large. But the game is changing nearly as fast as sea levels are rising. Hurricanes, which have been increasing in frequency and intensity in recent years, have condensed years of erosion into single events.

“Shell Bluff Landing was scheduled to be scanned annually,” Murray said. “But Hurricane Ian changed it so dramatically, and permanently, that we have to rescan it sooner.”

According to Murray, these sites likely contain important information not just about the past, but also have implications for the future. Surveying these sites before they are lost provides clues on how human populations have adapted to Florida’s erosion over the years.

“We can learn how people moved and reacted to erosion in the past, including which methods worked and which didn’t,” Murray said. “To understand the past is to understand the present. We learn how we got here, and now, where we’re going.”