A Garry oak tree (also called a “white oak”) is a species responsible for creating one of Canada’s richest ecosystems. Home to over 100 threatened plant and flower species, the so-called “Garry oak ecosystems” are unfortunately, themselves, also endangered, with just 5%, of Garry oak ecosystems in Canada surviving today in their natural state. They are one of the 4 most endangered ecosystems in Canada.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) is interested in preserving these Garry oak ecosystems, because of the many unique species they nourish. On Vancouver Island in western Canada, NCC is the steward of a 50-acre Garry oak ecosystem called the Cowichan Garry Oak Preserve. NCC provides opportunities for researchers to help preserve these fragile ecosystems, and for volunteers to assist with monitoring and maintaining the endangered plants that they host.

Throughout the year, about 12 volunteers spend one morning per week within the preserve. There, they perform work that gives surrounding endangered species a chance to thrive. This work includes:

- monitoring plant populations around the Garry oak trees,

- recording annual flower counts,

- planting native species,

- collecting seeds from endangered species,

- pulling invasive species,

- and maintaining a native plant nursery.

The end goal is, of course, the preservation of the Garry oak trees themselves, the ecosystems they anchor, and the endangered species contained therein.

The Challenge: Manual Measurements Make Returning to Specific Trees Tedious

Every five years, measurements (such as precise flower counts) are taken to assess the health of the Garry oak ecosystems. This work takes place necessarily during the spring and summer.

Summer is when tall grasses thrive in western Canada, and this can make locating specific species very difficult.

Traditionally, the volunteers and researchers have relied upon a system of physical identification tags and pins to locate the 45 individual Garry oak trees and the endangered species around them. The typical process goes as follows: First they locate the tagged Garry oak trees; the tags contain written angle and distance measurements that help guide the volunteer or researcher from the tree itself in the direction of a specific endangered plant, or plants, within the ecosystem. The plants themselves are tagged with marker pins, but because of the tall summer grasses and the natural evolution of flora, relocating these plants has proven often challenging. Sometimes a marker could be missing, making finding surrounding plants difficult.

“It could sometimes take up to 10 minutes to locate the research site — even when the tree and its marker are intact,” Volunteer Site Supervisor Larry White said. “Moreover, if one of those markers goes missing, it could take up to an hour to identify the plot site.”

Without a digital record of these research plots, a volunteer or researcher has no recourse for continuing their research in case a marker goes missing, a tree falls, or if other natural factors limit their work.

All of this impacts the results of their efforts and, in turn, their ability to update NCC’s conservation team.

“Historical data of these flower counts can be suspect, because over time, natural changes to the environment can make it difficult to know if you are returning to the exact location where the researcher was five years ago,” White said. “Our manual measurements from the marked reference points are usable, but the accuracy has been deteriorating.”

The Solution: High-Accuracy Digital Mapping Tools

In 2019, White reached out to Canadian GNSS manufacturer Eos Positioning Systems to inquire about a high-accuracy GPS receiver that could help to digitize the volunteers’ research records. Capturing Garry oak tree locations digitally, with high accuracy, could ensure researchers confidently returning to Garry oak ecosystems within the preserve for many years into the future.

“I had absolutely no prior experience or training with GIS, so I was surprised how easy it eventually wound up being to adopt mapping software with the Arrow GNSS location accuracy,” White said.

Without the accuracy of the Arrow 100®, it would not be possible to locate and harvest seeds from these plants at a time in summer when they would not normally be visible amongst the tall grasses.

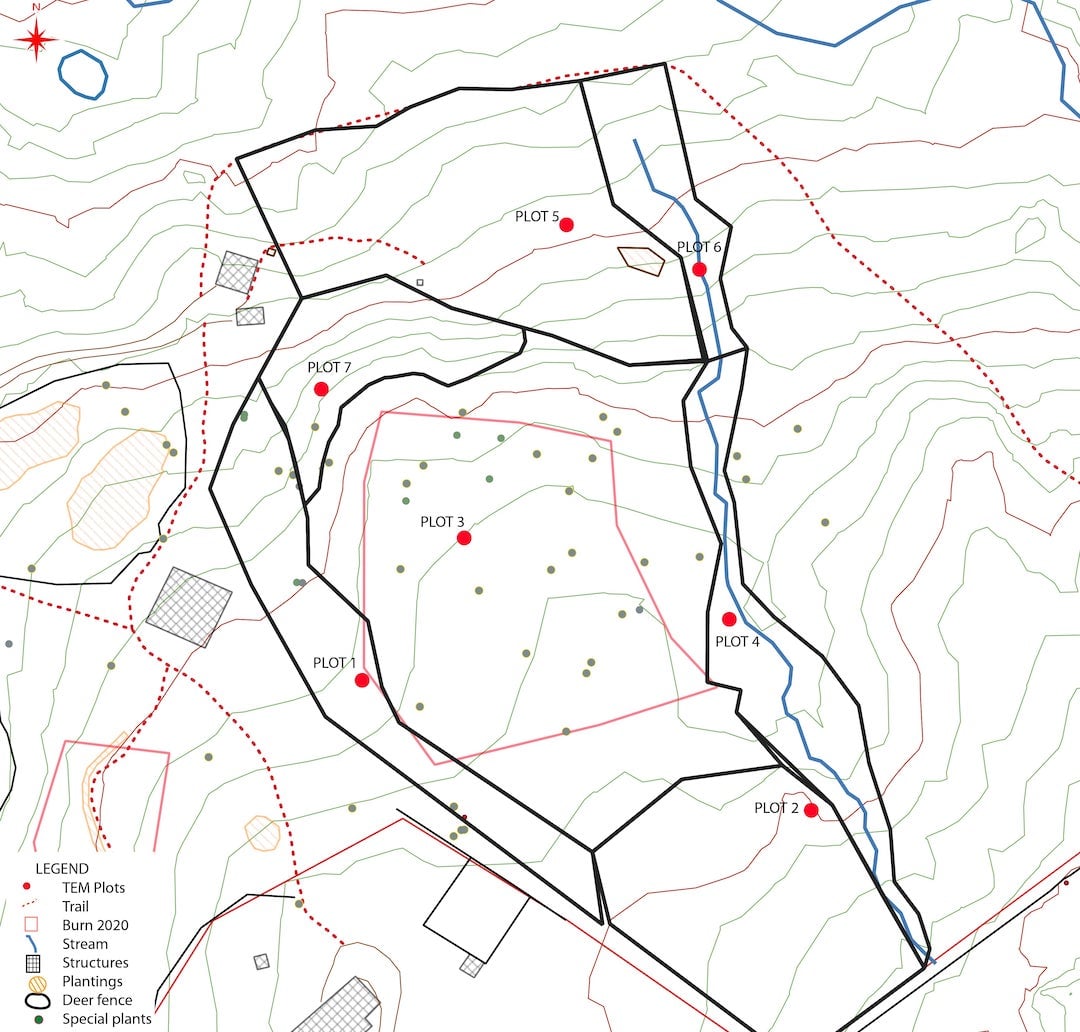

White purchased an Arrow 100® GNSS receiver from Eos, which could provide consistent and reliable submeter-accurate location data to the outdoor navigation app Gaia GPS running on personal iOS® and Android cell phones. The Arrow 100® does this by taking advantage of the free WAAS Satellite-Based Augmentation Systems (SBAS) differential corrections. These submeter locations, sent via Bluetooth to the volunteers’ smartphones, were collected as waypoints in the Gaia GPS app to map the Garry oak trees and the various plant species. The waypoints, in turn, were transferred to an open-source Geographic Information System (GIS) software called QGIS. The resultant digital maps effectively showed where every research plot was with extreme accuracy. The maps could be used to navigate to the exact same Garry oak tree, over time, with high confidence. The research collected there could also be more easily shared digitally with the NCC and its stakeholders.

“With the Arrow 100®, we now have the ability to collect and permanently store this data for future generations, all on one map,” White said. “Annual reports are prepared for the site in QGIS and submitted to the NCC. At the local level, we now have a permanent record of a variety of activities and features.”

The Results: Garry Happy

To date, the volunteers have used the new digital record-keeping solution to begin tracking the following data with higher accuracy:

Flower Counts:

- Recording flower counts for 71 populations of 5 species.

- Mapping larger populations of 4 species that are either extremely rare and/or extremely difficult to identify once they have lost their flowers and gone to seed.

Endangered Seed Data Collection:

- Location data is attached to endangered species seed collection.

Rare Fungi Research:

- Supporting research for rare mycorrhizal fungi (mushrooms) that are specific to Garry oak ecosystems, some of which have never been identified before.

Plot Maps:

- Mapping plots where there have been mass plantings.

Mapping Boundaries as Polygons:

- Recording boundaries of research plots.

- Recording boundaries for controlled burns. Controlled burns, carried out by the British Columbia (BC) Wildfire Service, are used to control invasive species and improve the condition of the meadows. This practice is based on the long history of burning done by indigenous communities in the area, who used fire to encourage the growth of edible plants, among other benefits. Volunteers plot the boundaries and submit the data to NCC, who work with the BC Wildfire Service to develop an official burn plan for six plots.

- Plotting boundaries for major restoration projects. These projects will take multiple generations to complete. (For instance, a Garry oak tree that grows 2-3 cm per year might take centuries to reach mature height and canopy.) NCC volunteers can now monitor the progress of these restoration projects, assess past activities, and identify what still needs to be done.

Terrestrial Ecosystem Mapping:

- Recording features pertaining to terrain, soil, and plant communities. In 2021 alone, volunteers mapped and recorded research at seven micro-habitats. One of these micro-habitats appears to be appropriate for supporting two of the rarest species in the preserve, so testing has begun in fall of 2021 to confirm this.

General Mapping of Features:

- Volunteers are mapping natural features (e.g., streams, creeks) and built features (e.g., roads, buildings, trails).

Although their work takes a lot of dedicated time in the field, White says it is worth it. The volunteers’ research has contributed to many meaningful insights into the endangered species contained within.

For instance, flower-count data helps inform management actions which encourage springtime regrowth of the same flowers.

“We are now continuing to monitor flower counts to see if mowing woody shrubs and grasses has the same positive effect as burning,” White said.

The result of other flower counts, which indicate population reduction of certain endangered species, have been used to justify fencing installation to keep out non-native rabbits.

In addition, the volunteers have used the technology to map out proposed plots that are particularly suitable to sustaining specific species. As climate change introduces changes to the ecosystems, this data can be used to potentially replant at-risk species to ensure long-term survival.

At the heart of all this work are the volunteers who persistently revisit the preserve to perform the surveys and maintenance. This digital transition that now brings higher confidence and repeatability in their work, makes the prognosis for their efforts more promising and rewarding.