Just off the southern coast of South Carolina, Edisto Island was named for an Indigenous sub-tribe of the Cusabo peoples. The Edisto people used the island for settlements and fishing. With a population estimated at 1,000 in the year 1600, the Edisto people eventually disappeared by the 1800s, due to European settlement and disease.

Today Edisto Island is home to important artifacts, including unique pottery such as Thoms Creek pottery sherds (a “sherd” is a piece of pottery, not to be confused with a “shard” which is a piece of glass) and mysterious shell rings, which are structures built of oyster shells and other shells. Shell rings still hold many archeological mysteries about the earliest inhabitants of the southeastern United States, but these un-excavated artifacts are at risk of being lost to the ocean, due to rapid coastal erosion.

“In the past 70 years, Edisto Island has seen about ¾ of a mile of shoreline loss,” said Meg Gaillard, a Heritage Trust Archeologist for the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR), citing this ArcGIS StoryMap which visually documents the South Carolina coastline’s erosion from the earliest known records.

The SCDNR’s Heritage Trust Program was founded in 1974 with a mission to “preserve and protect natural resources, for current and future generations.” Today the Heritage Trust Program archeologists assist with cultural resource management across the state. The SCDNR is responsible for over 1.1 million acres, and over 200,000 of those acres are coastal.

Due to fast-paced erosion, there is an obvious question about carrying out such a mission along the coast.

“Our legal obligation is to protect these resources for current and future generations,” Gaillard said. “But the question we are facing today is, ‘What happens when we can’t?’”

The Challenge: A Race Against Time to Excavate Coastal Artifacts

Eos Positioning Systems interviewed Gaillard while she was conducting research at a site adjacent to Pockoy Island in December 2021. The Pockoy Island Shell Ring Complex consists — or rather, used to consist — of a set of two shell-ring structures. These rings were discovered in late 2016 during a LiDAR scan of the coast taken after Hurricane Matthew. The two shell rings date back to 4,300 years ago, making them contemporary with Stonehenge and Egypt’s first Great Pyramid.

Since 2017, SCDNR archeologists have been racing to excavate the Pockoy Island Shell Ring Complex.

“We’ve been doing these excavations while knowing full well that we would lose this site within our careers,” Gaillard said.

In fact, in 2017, Dr. David Anderson of the University of Tennessee-Knoxville and his colleagues, published a paper detailing a predictive model that estimates at least 13,000 known archeological sites in the southeastern United States alone will be lost to erosion in the next 100 years.

“That’s significant, because the Pockoy Island site became known to us just recently,” Gaillard said. “It’s hard to imagine how many cultural sites we might lose that have yet to be discovered.”

According to Dr. Anderson, this is a threat not unique to the southeastern United States, but rather a challenge for humanity globally. Archeological investigation is one of the only ways to ensure the preservation of records for future generations.

“The SCDNR research team’s efforts to rescue information from vanishing coastal sites is exactly the kind of proactive action needed if our descendants are to have any appreciation for how life used to be in coastal areas,” Dr. Anderson said. “While many will rise to the challenge, this is an important example showing us all how to proceed.”

Today, Gaillard and her SCDNR archeology colleagues have become passionate advocates for monitoring and mapping shoreline erosion with extremely precise measurements. By having reliable shoreline maps over time, it is possible to prioritize known excavation sites that may be lost in the near future.

“If we can excavate these sites today, before they are lost, then research on the excavated artifacts will be possible in a museum or a curatorial facility at a later date,” Gaillard said. “It’s an opportunity for future researchers to be able to say something about these cultures that came before us.”

Did you know?

More information about this site and other shell-bearing sites can be found in the documentary The Ring People and supplemental short documentary films.

The Solution: Measuring Shoreline Loss with Extreme Accuracy to Prioritize Excavation Sites

To prioritize excavation sites in the future, Gaillard and her colleagues wanted a highly accurate, irrefutable method of measuring shoreline loss.

“Being able to have really accurate measurements is critical,” Gaillard explains. “We want to be able to say, at a conference for instance, that we are not just guessing at the measurement of shoreline loss. We are certain this site is gone, or is highly likely to completely erode away in coming years. Quantifiable data lends credibility to anything we say.”

In 2018, Gaillard and her SCDNR archeology colleagues learned that SCDNR’s GIS Manager Tanner Arrington was using a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receiver to enhance the accuracy of his mobile mapping work. She borrowed Arrington’s device, an Arrow Gold® GNSS receiver made by Canadian company Eos Positioning Systems, and tested it for shoreline mapping.

“Just knowing that this technology was out there, we had to have it,” Gaillard said.

In September of that year, the Heritage Trust Program purchased their first of two Arrow Gold® GNSS receivers for shoreline mapping.

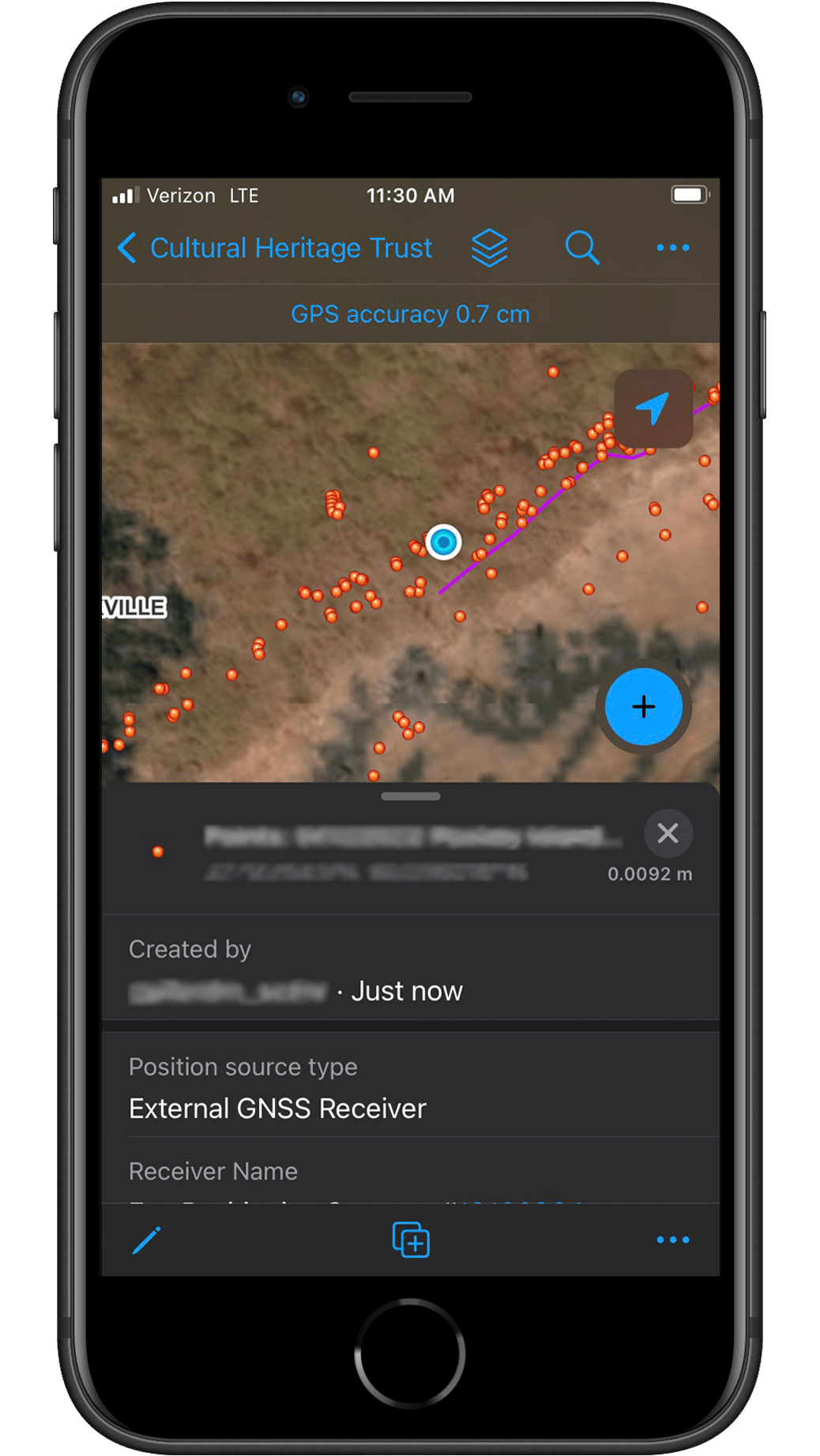

At Pockoy Island, Gaillard uses Esri’s ArcGIS Field Maps (formerly ArcGIS Collector) on both iPhone® and iPad® to collect data points as she walks along the beach and climbs across fallen trees marking the space where land and sea meet. The Arrow Gold® sends centimeter-level accurate horizontal and vertical positions to Field Maps via Bluetooth®, along with useful GNSS metadata.

Back in the office, Dr. Karen Smith, SCDNR archeologist and lead on the Pockoy Island Shell Ring Complex excavations, digitizes a line from Gaillard’s points. The resultant shoreline can be compared to earlier measurements. Over time, the team can see where erosion is most rapid. And because the measurements are extremely accurate, Smith and the team, including Eastern Tennessee State Assistant Professor of Anthropology Dr. Lindsey Cochran, can predict which land might be underwater by the next planned excavation season. Dr. Cochran and Gaillard have been using this modeling since 2020 (they did not use the modeling on Pockoy Island itself, which had already undergone multiple seasons of field work prior to the collaboration’s beginning).

“While predictive modeling of the impact of shoreline change is never perfect, the output maps give us a great place to start identifying areas that are most susceptible to damaging changes from the ongoing and intensifying climate emergency,” Dr. Cochran said. “Every model needs to be ‘groundtruthed,’ which is the act of archeologically verifying digital predictions to see if what I see on a computer screen matches what SCDNR archeologists see in the dirt.”

Based on the models Dr. Cochran creates, the team builds an excavation plan to prioritize the next season’s sites.

“Without these boots-on-the-ground measurements and predictive models, we would be flying mostly blind,” Gaillard said. “With them, we can see the shifts in what is being lost and what is somewhat stable. And we can try to put excavation units in ahead of the loss, knowing for a fact that the parts of the site we excavate this season will be under the Atlantic Ocean come next season.”

The Results: Shell Ring 1 is Gone, But Its Artifacts Survive

The Pockoy Island Shell Ring Complex is a literal race against time.

“Ring 1 is completely gone,” Gaillard said. “Never to return.”

The data show that Pockoy Island’s erosion rate has been increasing since 2016. According to calculations by SCDNR Coastal Geologist Katherine Luciano, Pockoy Island will be completely eroded by 2037.

“That’s very rapid,” Gaillard said. “We have a finite amount of time to work. This is why technology like the Arrow Gold® is so important to us. Without it, we’re just guessing which places to prioritize for excavation.”

Looking Ahead: Erosion is a Global Concern

Gaillard and her team collaborate with organizations facing similar challenges worldwide. In May 2019, archeologists Tom Dawson and Joanna Hambly from the Scottish Coastal Archeology and the Problem of Erosion (SCAPE) and Scotland’s University of St. Andrews visited the Pockoy Island site. They have been monitoring the shoreline of Scotland for many years.

“This is not just a southeastern United States problem,” Gaillard said. “It’s a global effort to stay ahead of erosion.”

The SCDNR has also developed partnerships with the Florida Public Archeology Network (FPAN), who run Florida’s Heritage Monitoring Scouts (HMS) program, which was modeled after shoreline monitoring working already underway in Scotland. According to Gaillard, FPAN is leading when it comes to incorporating community stakeholders in their work. FPAN meets regularly with a representative of the northeastern Florida Gullah/Geechee Nation, Glenda Simmons-Jenkins, to coordinate both parties’ priorities.

“I think it’s important we, as professionals and academics, align our priorities to the communities we serve,” said FPAN Regional Director Sarah Miller.

Through Simmons-Jenkins, the Gullah/Geechee Nation has shared concerns with FPAN about the disturbance of sacred burial sites, environmental impacts from climate change, and restorative justice. According to Miller, this discourse provides a clear priority for FPAN, which can help ensure Gullah/Geechee burial sites are accurately mapped, which in turn fills data gaps for planners and reviewers who in the future might make important decisions that impact these local communities.

“It can’t be said enough in our work, you can’t manage what you don’t know is there,” Miller said. “Confirming the location of sites is the number-one thing we can do to help manage heritage at risk along our coastlines.”

We barely ever use paper anymore. We’ve gone completely digital. We’re using our iPads, iPhones, Arrows, and the Esri platform. I don’t know how we would do our job on heritage at-risk sites like Pockoy without being able to use this technology.

Gaillard calls her colleagues from Scotland and Florida an inspiration. She hopes to emulate the standard FPAN has set for proactively incorporating community feedback into their work.

“Florida is leading on this, and we hope to be right on their bootheels, because time is of the essence,” Gaillard said. “We’re in early conversations with Tribal representatives who are interested in the Pockoy Island site. We want to know if they want us to excavate sites on their ancestral land, or if we should let them go. These are questions we don’t have answers to yet, but measurements will be critical.”

Gaillard says there are many reasons why a site would not be excavated, including limited storage capacity for artifacts. Everything excavated from an archeological site is, by law, required to be curated in perpetuity.

“We are not going to be able to excavate and curate the artifacts from all of the at-risk cultural sites we are currently aware of to the extent we have at Pockoy Island,” Gaillard said. “But by using the Arrow Gold® and other technologies, we can at least measure the loss. We can also discuss with colleagues and the public the rate of loss, as well as the decisions we make as cultural resource managers as to which sites we do choose to excavate, like Pockoy, and why we choose not to excavate others.”

Gaillard says the technology has made the Heritage Trust Program’s mission more possible.

“I can’t tell you how much we’ve been using our Arrows and iPhones,” she said. “We barely ever use paper anymore. We’ve gone completely digital. We’re using our iPads, iPhones, Arrows, and the Esri platform. I don’t know how we would do our job on heritage at-risk sites like Pockoy without being able to use this technology.”

What Kind of Artifacts Come From Pockoy Island?

On Pockoy Island, it is not only the types of artifacts that make the site unique, but also their quantity.

Two of the earliest forms of pottery in North America are found on Pockoy Island: Thoms Creek and Stallings Island sherds. These sherds were formerly decorated with periwinkle shells and ends of reeds and canes. “They are incredibly unique and beautiful,” Gaillard says.

Use of stone was not common along the South Carolina coast, so the Heritage Trust Program also found lots of bone and shell artifacts, such as hand-carved deer-bone pens and shell tools. Indigenous people would have punched a hole in a whelk (a sea shell similar to a conch), for instance, and stuff a stick inside to create an ax-like tool known as an adze. Adzes were probably used to cut down trees and build canoes.

“So many different people on our team study each of these items,” Galliard said.

The Secrets Sherds Hold

SCDNR Archeologist Catherine “Cate” Garcia wrote an article for SC Wild showcasing specific artifacts found at Pockoy Island. Discover the secrets of Shell Rings’ sherds here: “Reconstructing Pottery from the Pockoy Island Shell Rings”

Excavate Bone Pins on Edisto Island

Follow Kiersten Weber and the SCDNR on a journey into what it’s like to excavate bone pins on Edisto Island, and discover what we can learn from these thousands-years-old artifacts: “Researching the Late Archaic Bone Pins of South Carolina”

How Are Artifacts Located?

In May 2019, the SCDNR Heritage Trust Program supervised university students who surveyed Pockoy Island to identify additional sites. They walked along transects of a grid and dug “shovel tests” at regular intervals 10 meters apart. The shovel test provides a window into the ground. It lets the students see, and record, if there are any artifacts or features. They capture the data — such as type and quantity of artifacts, soil color and consistency, and photos — in an ArcGIS Survey123 form, created by Arrington and Smith, on their SCDNR-issued iPhones. The accuracy of the shovel test locations is provided by an Arrow 100® GNSS receiver, which connects via Bluetooth® to the iPhones and provides submeter-level accuracy. The grid was laid out and the location of every shovel test was flagged by Smith prior to the students arriving on site.

Gaillard likes the mobile setup because it allows real-time artifact data collection.

“On a site like Pockoy Island, which is being lost so rapidly, that is absolutely essential during a month-long field season,” Gaillard said. “We can quantify artifacts rapidly, knowing we might experience a king tide event mid-season that impacts our work. So we can say, for instance, if we are seeing a higher density of artifacts in particular places on this site we have only shovel tested, we might have an opportunity to refocus our efforts quickly to put in some larger excavation units before we lose that part of the site.”

The real-time data collection also adds a layer of safety for the students.

“Not only does this let us work rapidly, but it also lets us work more safely, because some students have never worked in a marine forest setting before,” Gaillard said. “We can track their locations, and that brings us an element of safety.”

Each season, K-12 students also visit Pockoy Island to help archeologists sift soil for artifacts. Later on, students can visit the SCDNR archeologists in their lab in Columbia, S.C. where they can help wash the artifacts they helped uncover in the field.

“This is really full circle for me, when the little kids can come to help us,” Gaillard said. “Their efforts really do matter, because where they stood at those sifting screens only a year and a half ago is now underwater. But what they helped save might one day be on display in a nice museum case, and stored in the SCDNR curation to be researched for generations.”