High-Accuracy Mapping Technology Confirms a Long-Suspected Tragedy

On July 15, 2021, Dr. Sarah Beaulieu walked up to a podium to confirm a heavy history at a press conference.

Beaulieu, Assistant Professor in Anthropology and Sociology at the University of the Fraser Valley, was reporting on the findings of roughly 200 potential unmarked graves of Indigenous children at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada. The Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation made the discovery with Beaulieu by conducting a ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey on the school grounds. At the press conference, Beaulieu combined oral history and technologically supported evidence to report on the long-suspected tragedy.

The news made headlines around the world, setting off a chain of outrage followed by calls for assistance to conduct similar surveys at the 139 total residential schools that operated across Canada in the 19th and 20th centuries.

A Dark, Century-Long History of Indigenous Residential Schools

The Canadian government-sponsored Indigenous Residential Schools were founded in the 1880s, and in 1894, amendments to the Indian Act deemed it mandatory for all Indigenous children to attend these schools. This requirement continued until 1947, but many schools remained in operation until the late 1990s. During more than a century of operations, these schools housed over 150,000 children.

Children were forced from their homes and stripped of their culture. The schools suppressed and often banned Indigenous languages, religion, and dress. These tactics were key in the compulsory assimilation of Indigenous communities.

While reports of abuse, neglect, disappearances, and deaths of children had long been known and passed on within Indigenous oral history, these facts were largely ignored by mainstream media until recent movements to scientifically uncover the truth and seek reparations.

“Evidence has existed in government and church archives for more than a century,” said Beaulieu in the press conference. “Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report [the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015)] identified between 4,000 and 6,000 missing children but anticipated that these actual numbers would be much greater.”

Validating Stories of the Past — Refusing to Forget

Thus began a collective quest to amplify the stories that had been silenced for years — stories of children disappearing and never coming home. Stories of students being woken up in the middle of the night to dig their classmates’ graves. Stories that, for decades, Indigenous people were told to forget.

“It is important to note that remote sensing, such as GPR, is not necessary to know that children went missing in the Indian Residential School context,” Beaulieu said in the press conference. “This fact has been recognized by Indigenous communities for generations.”

By adding scientific data, high-accuracy surveying equipment, and remote-sensing tools, Indigenous communities hope to force the larger world, and even skeptics, to acknowledge what happened to these children in the not-so-distant past.

Combining Oral Tradition with Modern Science and Technology

As an Assistant Professor at the University of Frasier Valley, Beaulieu focuses on modern conflict anthropology. She is known for her work excavating World War I internment camps in Canada, where she discovered and mapped unmarked graves of prisoners of war using GPR technology.

Her experience in using GPR at unmarked burial sites led the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc First Nation to bring Beaulieu on to their original project in Kamloops. Now, Beaulieu is conducting similar surveys for First Nation communities across Canada.

Whenever Beaulieu is asked to contribute to a project, she seeks a respectful relationship between time-honored oral history, which provides records of what is believed to have happened, and the results of modern technology, which can provide evidence to what happened. All her work is conducted in accordance with Indigenous community traditions and their oral histories.

“Tk’emlúps describe this as walking on two legs,” Beaulieu said. “This means upholding both western laws and science as well as Secwepemc laws as laid out in oral histories and songs.”

To illustrate the harmony of walking on two legs, Beaulieu emphasizes that without the oral retellings of Indigenous communities, the science would not even know where to begin regarding the location of these surveys.

GPR: Looking Under the Surface

Beaulieu decided to bring in cutting-edge technology by using GPR and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) receivers to locate the burials with high accuracy. Because excavating the graves would violate Indigenous beliefs surrounding burials, Beaulieu was glad this technology offered a data-driven but protective surveying solution. GPR allows for non-invasive location of a grave’s existence, in accordance with Indigenous traditions, while remaining scientifically accurate.

GPR works by sending electromagnetic pulses into the ground, which echo back to the system once they hit an object. Different types of materials, such as buried anomalies, will reflect differently than the soil that surrounds them. These reflected signals and their velocities are then interpreted by the GPR and translated into a measurement showing the depth and size of the anomaly.

To conduct the GPR surveys, Beaulieu first divides the site area into a grid system. Each grid is divided into sections made up of 25-centimeter transects, marked by lines of string, which create a path for the GPR system. Beaulieu then follows these transects up and down like rows, while moving the GPR like a lawnmower, carefully covering every inch of the site.

Next, Beaulieu uses the GPR’s built-in software and display to process the results. The interpreted data appears on the screen as a radargram (patterns of reflections that indicate any abnormalities below the surface). Using this data, she looks for abnormalities that are consistent with a grave. When the contents of a grave are buried, it leaves behind subtle yet unique soil disturbances long afterward.

“When I’m reading these on the screen, I’m not seeing bones or human remains,” Beaulieu said. “I’m looking for soil displacements or subsurface anomalies. For burials specifically, often you’re not actually looking at the content of the burial itself. When you dig a grave and you replace the soil, the stratigraphy [analysis of the soil layers’ orders and positions] changes.”

These anomalies, or “hyperbolic responses,” have very different responses from other underground objects (including pipes, root systems, and stones). It is Beaulieu’s job to identify the signatures typical of a burial site.

Once she has identified these anomalies, Beaulieu then processes the GPR data using EKKO_Project™ GPR software to further analyze the data back in the office. This software allows her to process the GPR data, organize it, and use visualization tools to further analyze it through different displays and visualization tools.

GNSS: Adding Confidence to Data with High-Accuracy Locations

The scope of the Kamloops graves brought with it shock and disbelief. Despite the overwhelming oral and scientific evidence, public scrutiny still emerged across the internet, with many questioning the validity of non-excavated grave sites. Because of this, Beaulieu wanted to reassure Indigenous communities that the data she captured was as accurate as possible — in case they want to verify it in the future. As a result, Beaulieu sought to combine her existing GPR technology with high-accuracy GNSS receivers, which would pinpoint the exact location of each grave discovered with the GPR.

“Because the question of the burials is such a contentious issue, everything must be done to the highest level of professionalism and accuracy,” Beaulieu said. “Even beyond that, because everything we are doing is being scrutinized.”

Previously, Beaulieu had used the built-in GPS included with the GPR systems to associate her findings with physical coordinates. These findings were accurate to within a few meters. But with burials being so close together on the sites, Beaulieu realized that a few meters would not stand up to future scrutiny.

“Sometimes this data has to be able to hold up in court,” Beaulieu said.

After contacting several of her colleagues for GPS recommendations, Beaulieu selected the Eos Arrow 100® GNSS receiver made by Canadian manufacturer Eos Positioning Systems. The Arrow 100 provided submeter-accurate locations that could be referenced to the graves identified by the GPR. The Arrow GNSS receiver also had the capability to send its locations via Bluetooth® to an iPhone, where Beaulieu could use a field data collection app to capture these locations.

GIS: Choosing a Field Data Collection App

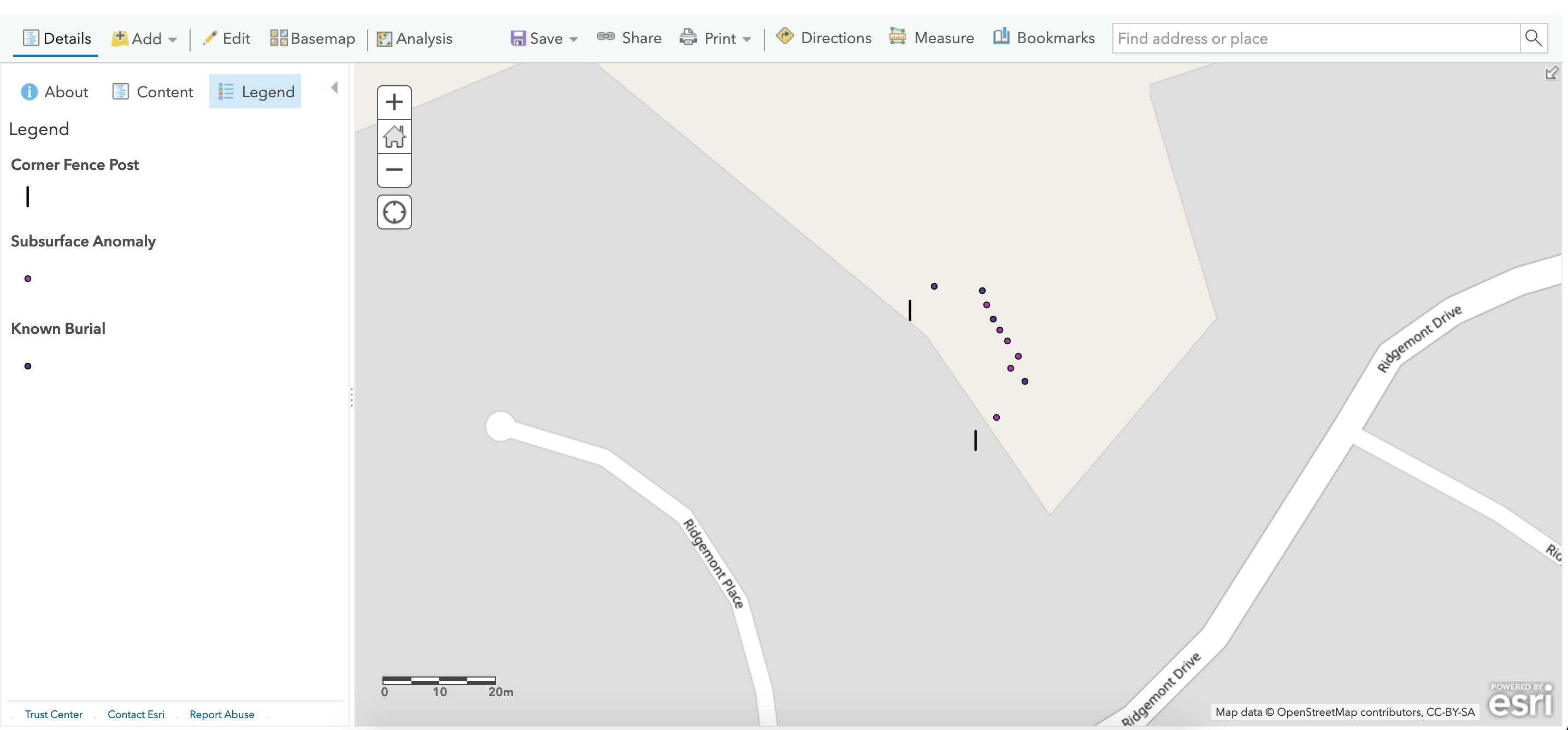

For a field mapping app, Beaulieu chose ArcGIS® Field Maps, a map-based data-collection application from global mapping software leader Esri. ArcGIS Field Maps takes the GPS coordinates from the Arrow 100 and collects them in a map. The Arrow 100 uses the free WAAS satellite corrections to provide submeter locations to Field Maps. This allows Beaulieu to easily map both grave locations and corners of her transect grid with high accuracy.

Because ArcGIS Field Maps and the Arrow 100 can work in a disconnected/offline mode (without internet connection), Beaulieu is able to map remote sites even when she has no phone signal. Before surveying sites, Beaulieu now downloads map areas on the iPhone to allow for uninterrupted work.

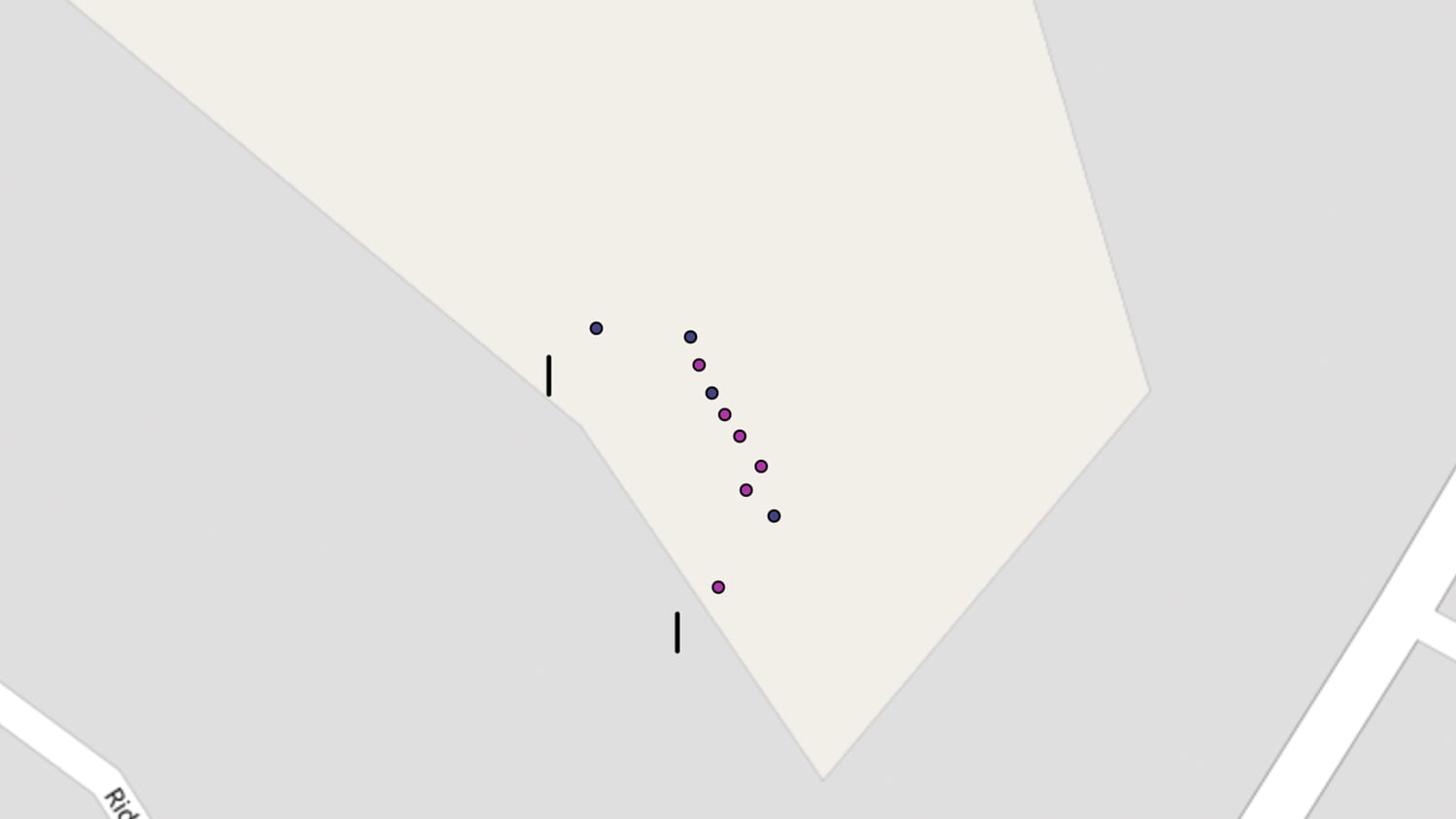

Once she surveys a site’s transect grid, Beaulieu can also revisit the site if needed. She sometimes does this after analyzing her GPR data to re-mark the locations of each burial with high accuracy for her reports. These points are stored in an ArcGIS Online map, and Beaulieu can then superimpose the GPR data onto the final map.

The final results can then be shared securely with interested parties, especially the First Nation communities. From there, it is up to the communities to use this data at their discretion.

“Whether it’s for commemorative purposes, to make sure people are not walking across these graves, or if excavations were to ever happen at any site — you want to know where these potential anomalies are,” she said.

Looking Ahead: Respecting the Past in the Present

With this new data-collection workflow, Beaulieu is now collecting the locations of potential gravesites at various Indigenous Residential School sites across British Columbia and other provinces. These points average 15 to 40 centimeters of accuracy.

Because of the need to respect those buried on these sites, she is careful to emphasize the importance of privacy regarding the exact locations of the burials. (For this reason, this article will not publish exact grave site locations.) However, the full location data and maps are shared with First Nations groups.

An added benefit of Beaulieu being able to share these digital maps is that now the First Nations can keep an accurate record of each burial without needing to visibly mark the locations on the ground. This prevents the possibility of any unapproved excavations from outside groups.

Beaulieu anticipates these projects will be ongoing for many years to come.

“I think this type of work needs to be slow and methodical,” Beaulieu said. “I don’t think it is something that can be rushed just for the sake of pushing for answers. There is more to this work than just looking for burials; there’s a trauma and re-traumatization that is happening and being felt.”

Beaulieu will look toward the Indigenous communities to guide her future surveys. With many of the residential schools consisting of hundreds of acres of land, these initial surveys are only the start of a long journey.

“Communities need to come together to decide what these next steps will entail — but this takes time,” Beaulieu said. “Using a high-accuracy GPS unit enables us to mark in the targets (anomalies) knowing that when each community is ready to continue with future work, they will be able to return to the precise locations and continue on.”